Introduction

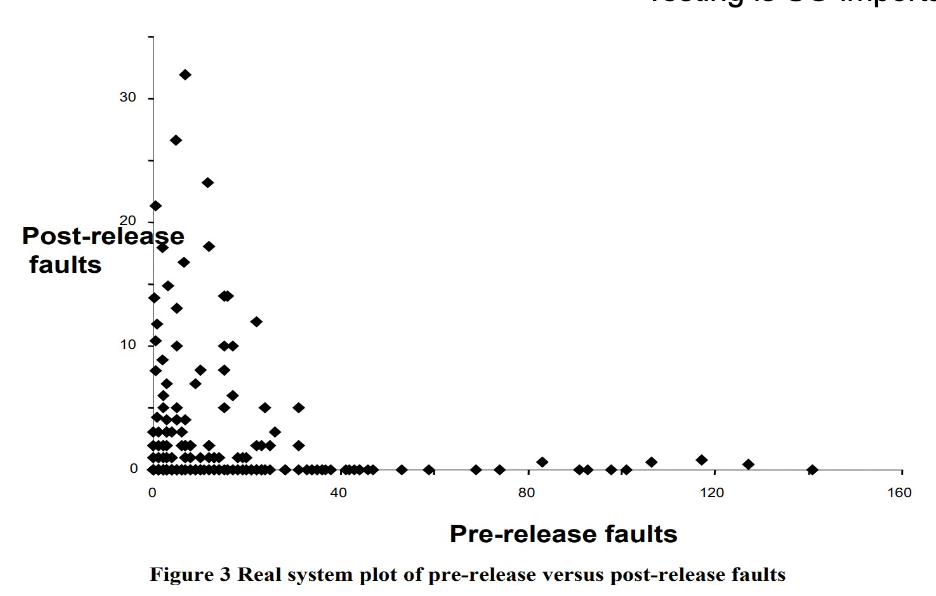

Testing is really important, as you can see by one of Norman Fenton’s results:

We will try to answer these questions:

- How can software size be measured?

- How can software structure be measured?

- Complexity metrics

- How can objected-oriented code be measured?

- What topics are related?

The Importance of Measurement

Measurement in software development serves three key purposes:

- Understanding: It helps us gain insight into the current activity, making it visible and allowing us to establish guidelines. For example, identifying methods or classes that are too lengthy.

- Control: Measurement enables us to predict outcomes and make informed decisions to manage and change processes effectively.

- Improvement: By establishing quality targets and measuring against them, we can continuously improve our software development practices.

Software Size

The size of software components is a crucial factor in software development, as it can impact its reliability and maintainability.

Measuring Software Size

One common measure of software size is Lines of Code (LOC). The larger a class, the more likely it is to contain bugs, making LOC a valuable metric.

Measuring Software Structure

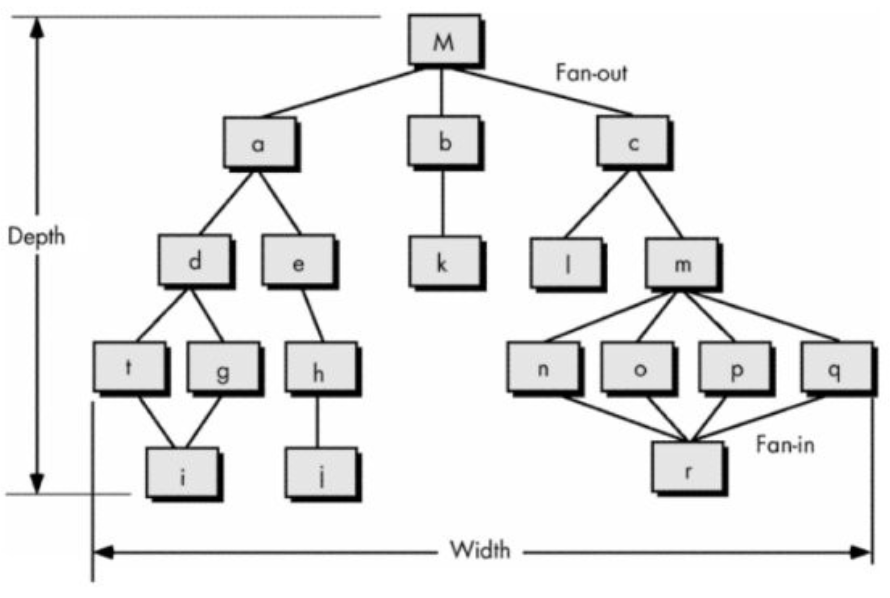

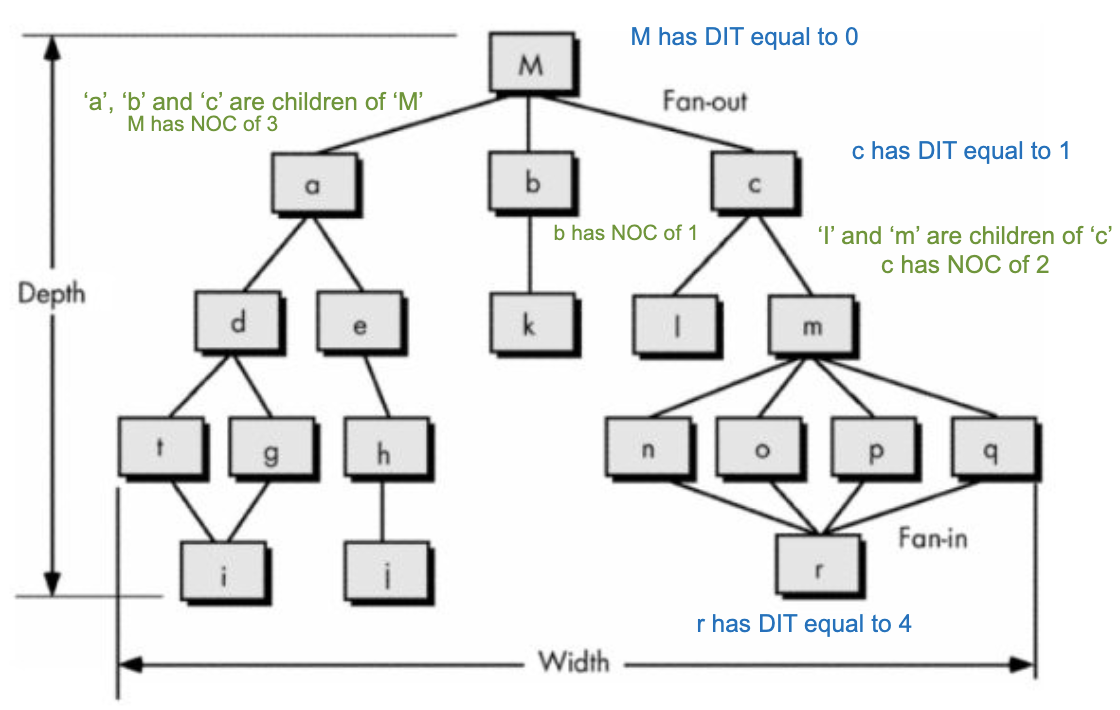

Information flow within the system:

- Indicator of maintainability and “coupling”.

- Identifies critical stress parts of the system and design problems.

- Based on:

- Fan-in: number of modules calling a module.

- Fan-out: number of modules called by a module.

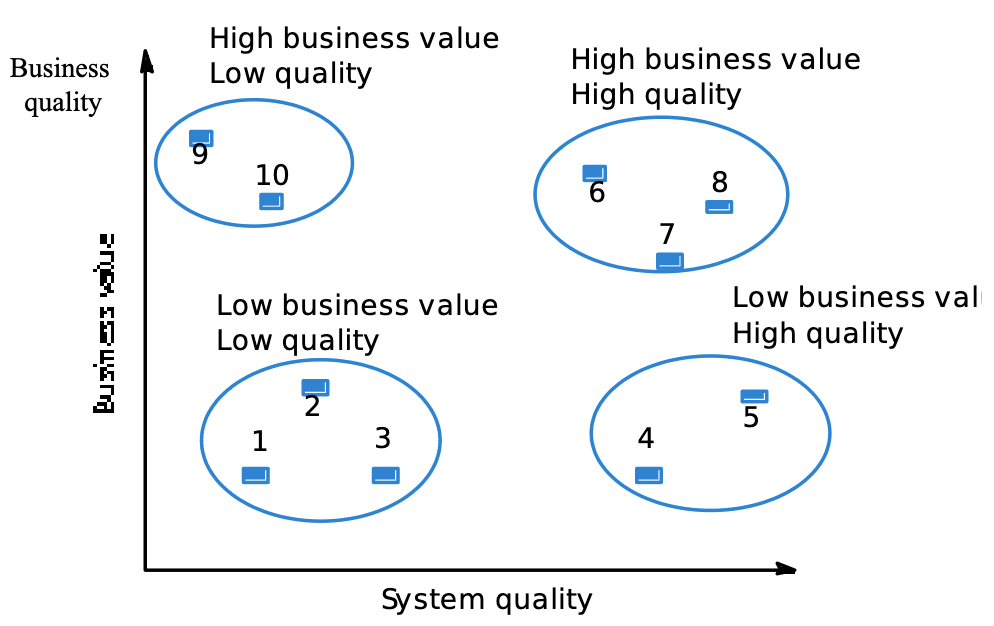

How Metrics Aid Decision-Making (an “audit grid”)

Complexity Metrics

Why use complexity metrics?

Complexity metrics, like McCabe’s Cyclometric Complexity Measure (CC), help in identifying:

- Candidate modules for code inspections.

- Areas where redesign may be appropriate.

- Areas where additional documentation is required.

- Areas where additional testing may be required.

- Areas for refactoring.

Henry and Kafura’s Complexity Metric

- A module X is 10 lines long.

- It has fan-in of 3 and fan-out of 2.

- Complexity of a

Therefore:

- Complexity of

McCabe’s Cyclometric Complexity Measure

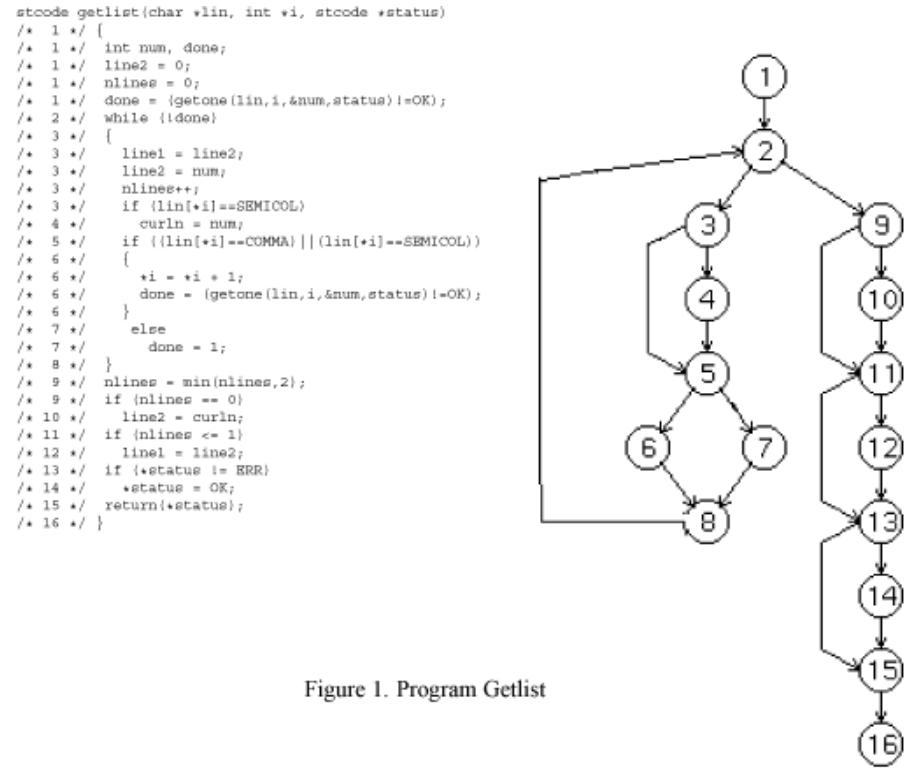

Used to measure the complexity of a program’s control flow. It qualifies the number of independent paths through a program’s source code. The higher the cyclomatic complexity, the more complex and potentially error-prone the code may be.

The formula is: where means edges and nodes.

Edges normally represent transitions between different parts of the code (e.g. branching statements like if-else or loops) and nodes represent decision points in the code where the control flow can change (e.g. conditions or loops).

- Commonly used by industry.

- In lots of tools.

- Based on control flow graph.

- Very useful for identifying white box test cases.

- Attributed to Tom McCabe who worked for IBM in the 1970’s.

Object-Oriented Metrics

How can OO code be measured?

- We will look at five of the six metrics of Chidamber and Kemerer (C&K).

- Developed in 1991:

- Weighted methods per class (WMC).

- Simple count of the number of methods in a class.

- Depth in the inheritance tree of a class (DIT).

- Level in the inheritance tree of a class.

- Number of children (NOC).

- Number of immediate sub-classes a class has.

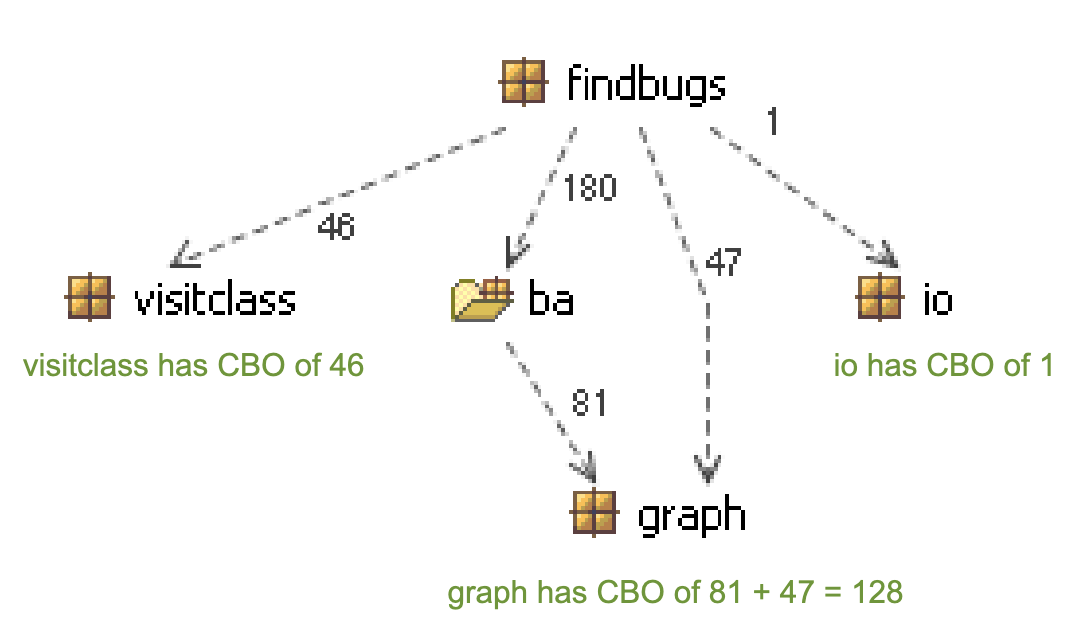

- Coupling between objects (CBO).

- Number of other classes coupled to a class.

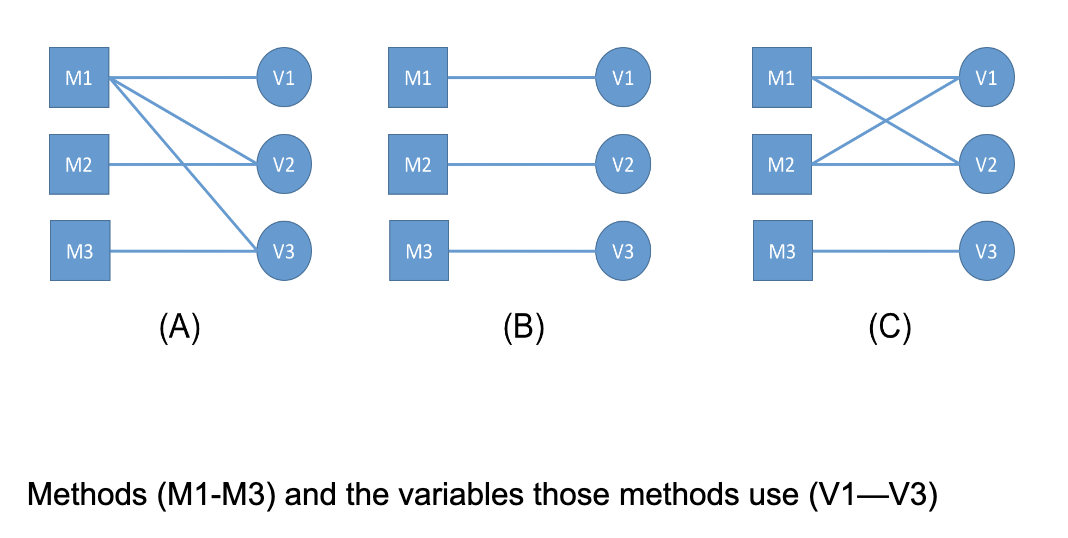

- Lack of cohesion of methods in a class (LCOM).

- Measure of how “well intra-connected” the fields and methods of a class are.

- Weighted methods per class (WMC).

The one missing is The Response for a Class but nobody really understands what it is trying to measure.

Weighted Method per Class

WMC measures the number of methods in a class, which can predict the effort required to maintain the class. Classes with many methods may be less reusable.

- The “weighted” part can be ignored.

- Simply the number of methods in a class.

- The number of methods is a predictor of how much time and effort is required to maintain the class.

- Classes with large numbers of methods are likely to be more application specific, limiting the possibility of reuse.

Depth in the Inheritance Tree of a Class (DIT) and the Number of Children (NOC)

DIT measures the level in the inheritance tree of a class, while NOC counts the immediate subclasses. Both metrics provide insights into code structure.

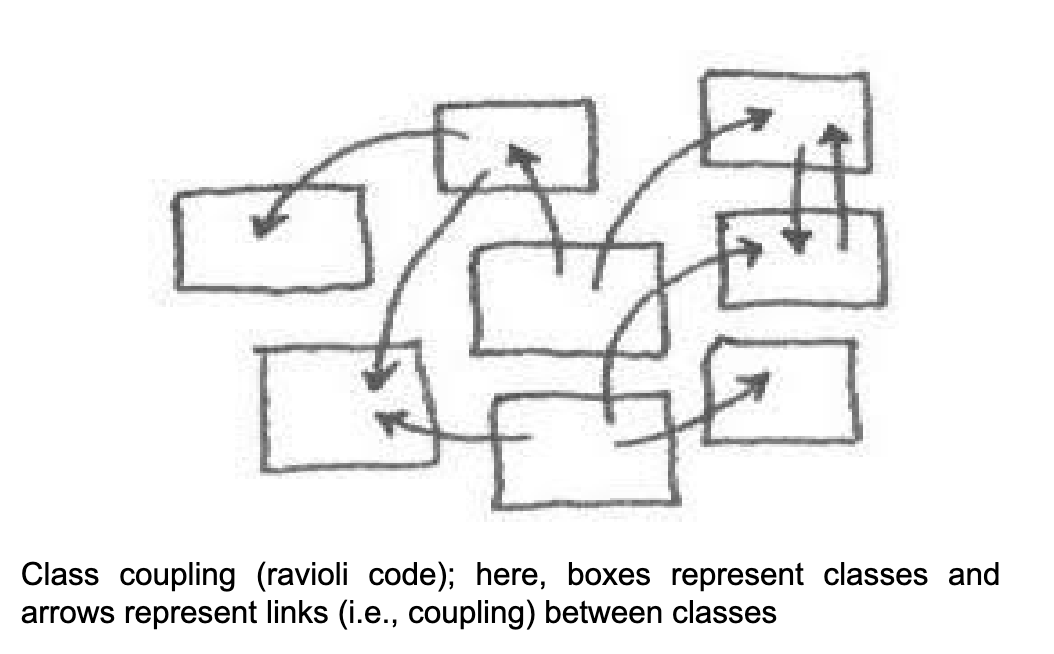

Coupling Between Objects (CBO)

CBO counts the number of other classes coupled to a class. However, it may not differentiate between types of dependencies, potentially leading to misleading results.

Lack of Cohesion of Methods in a Class (LCOM)

LCOM assesses the cohesion of methods within a class. Low cohesion can increase complexity and error likelihood.

- Cohesiveness of methods within a class is desirable, since it promotes encapsulation.

- Lack of cohesion implies classes should probably be split into two or more subclasses.

- Low cohesion increases complexity, thereby increasing the likelihood of errors during the development process.

Problems with metrics

- There is a tendency for professionals to display over-optimism and over-confidence in metrics.

- Metrics may cause more harm than good.

- Data is shown because it’s easy to gather and display.

- Metrics may have a negative effect on developer productivity and well-being.

- Academic/industry divide.

- Industry may be interested in specific aspects of their code (e.g. code churn).

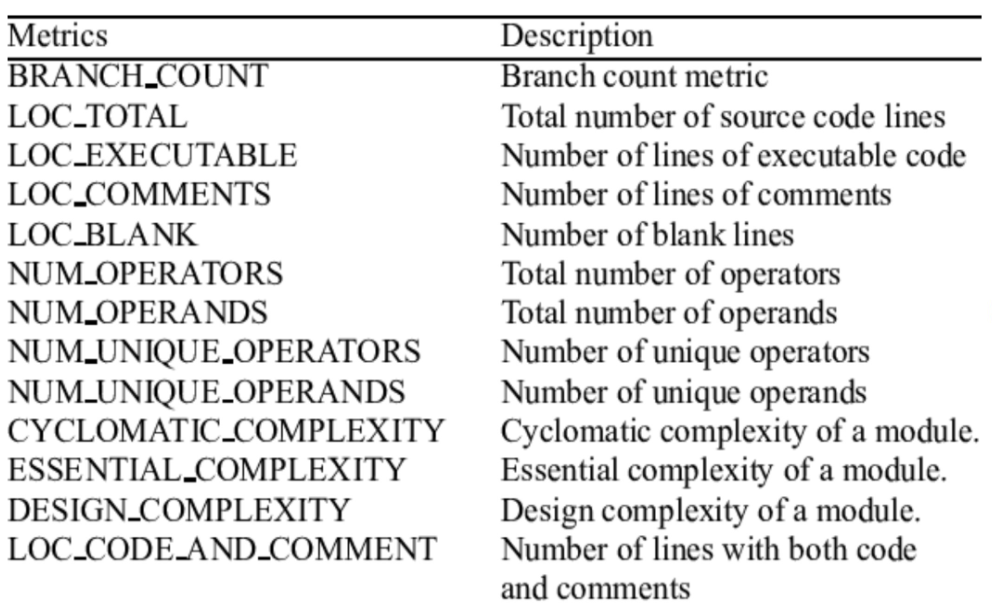

NASA’s Use of Metrics

- What do NASA use on their code?

- Cyclomatic Complexity.

- Lines of Code.

- Number of comments.

- Number of blank lines.

- Branch count.

- NASA has one of the best metrics collection programmes known.

Estimation by Analogy

Cost of a project computed by comparing the project to a similar project in the same application domain.

- Advantage: Accuracy when project data is available.

- Disadvantages: Impossible without comparable projects, requiring systematic cost data.

Questions

Q1) What do you think is the value of using software metrics to measure code?

Software metrics are valuable for assessing code quality, complexity and performance, aiding in early issue identification, optimisation and data-driven decision-making. For example, Cyclomatic Complexity (CC) and Lines of Code (LOC) can help developers identify complex and convoluted parts of the code that may be difficult to understand, maintain and debug.

Q2) Discuss one disadvantage of any four of C&K’s metrics of your choice.

- Weighted Methods per Class (WMC): it measure the complexity of a class based on the number of methods it contains. However, it doesn’t consider the actual complexity of those methods. In some cases, a class might have a high WMC due to simple, short methods, which might not necessarily indicate a problem. The contrary is also true, a class with a low WMC might still be complex if it contains a few very complex methods.

- Depth in the Inheritance Tree (DIT): it can be sensitive to design changes. Modifying the inheritance structure by adding or removing intermediate classes can significantly impact the DIT metric. This sensitivity can lead to instability in the metric and make it less reliable for assessing code quality.

- Number of Children (NOC): it measures the number of immediate subclasses a class has. However, it doesn’t take into account the depth and complexity of the inheritance hierarchy. A class with many shallow subclasses may have a high NOC but might not necessarily be problematic, whereas a single deep subclass could have a significant impact on maintainability.

- Coupling Between Objects (CBO): it counts the number of other classes coupled to a class. It can sometimes produces misleading results because it doesn’t differentiate between different types of dependencies. For example, it treats both method calls and attribute references as equal forms of coupling. Additionally, it may not account for dynamic or routine dependencies, potentially leading to inaccurate assessments of code complexity.

Q3) “Small classes are less likely to be fault-prone than larger ones.” To what extent do you agree with this statement?

It generally holds true, smaller classes tend to have advantages in terms of code quality and maintainability:

- Simpler logic: smaller classes tend to have simpler and more focused logic, making it easier to understand, test and debug.

- Single responsibility: they are more likely to adhere to a single responsibility, meaning that a class should have only one reason to change, resulting in less complex and more modular classes.

- Easier testing: smaller classes are easier to test in isolation because of the fewer dependencies and interactions with other parts of the code.

- Improved maintainability: smaller classes are generally easier to maintain and refactor.

However, other factors also determine the fault-proneness. For example: code design, adherence to best practices, code review processes and testing strategies.

Reading

- Sommerville - Chapter 24.

- Line of Code (LOC):

- Why LOC is not good as a measure see: http://www.inf.u-szeged.hu/~beszedes/research/SED-TR2014-001-LOC.pdf

- Cyclomatic Complexity: http://geeksforgeeks.org/cyclomatic-complexity/

- C&K metrics:

- http://virtualmachinery.com/sidebar3.htm